1A. CONTEXT/ RATIONALE: READING IN THE WORLD TODAY

In a former age, it made sense to read into a text and to stop our reading at the book’s back cover. We wrote papers about a single text and submitted these papers for no larger audience than the teacher or professor who read our interpretation of the text. Once upon a time, it might have made sense for others to read for us–to show us what was then considered the best reading of a text.

But times have changed. Today we live in a digital world which allows for–and even requires–new ways of reading. Hypertext means that we can literally read through the text. We can connect texts, and we can use our readings of texts to reach large audiences. As readers, we are hyper-connected to other readers and writers.

Today we read the world. Through social media and other forms of media, we can see global politics playing out in real time. We are the readers of history, in the moment-to-moment of its occurrence. We are also contributors, who can use voice and agency to create impact.

Updated literacy skills are not only appropriate to the age in which we live, they are all essential to the preservation of our democracy, which is dependent on the abilities of citizens to read the world well–and to use their agency/voice to participate, including through voting.

We need to nurture readers who know how to read the world today. The old reading skills are not enough for a world in which social media has created pathways for individuals and governments to use the medium of social media–and tools of language, narrative, and image/video/audio–to manipulate readers.

We need readers who can be savvy to the world of storytelling in the world today, including in a world where stories are generated through social media channels as well as other media outlets. We need readers who are not duped by propaganda and who know how to take in information to create a full and complex reading, one that evolves through ongoing civil discourse and further reading.

Imaginative literature remains a rich source of material that offers infinite possibilities for exploration and discovery. Our approaches to imaginative literature–and how we help students read it–need to shift. This site will offer ideas about shifts that can be made.

1B. SOME SUPPORTING THEORY AND RESEARCH

THEORISTS

James Moffett

Rita Felski

“More and more critics are venturing to ask what is lost when a dialogue with literature gives way to a permanent diagnosis,when the remedial reading of texts loses all sight of why we are drawn to such texts in the first place” (“Introduction,” Uses of Literature, 1)

” . . . how do scholars of literature make a case for the value of what we do? How do we come up with rationales for reading and talking about books without reverting tot the canon-worship of the past?” (2).

“. . . as teachers and scholars charged with advancing our discipline, we are sorely in need of more cogent and compelling justifications for what we do” (3).

Maxine Greene

” . . . encounters with literary works of art make it possible for us to come in contact with ourselves, to recover a lost spontaneity. . . By allowing ourselves to enter the imaginary mode of awareness, we submit ourselves to the guidance of an author as we lend a book some of our life” (“Preface,” Landscapes of Learning, 2).

“. . . I am interested in trying to awaken educators to a realization that transformations are conceivable, that learning is stimulated by a sense of future possibility and by a sense of what might be” (3-4)

“The point is that learning must be a process of discovery and recovery in response to worthwhile questions rising out of conscious life in concrete situations. And learning must be in some manner emancipatory, in the sense that it equips individuals to understand the history of the knowledge structures they are encountering, the paradigms in use in the sciences, and the relation of all of these to human interests and particular moments of human time” (19).

John Dewey

Paolo Freire

Louise Rosenblatt

RESEARCH

Metacognition and the value of transfer (excerpt provided by Mindshift):

Excerpted from “Four-Dimensional Education: The Competencies Learners Need to Succeed,” by Charles Fadel, Bernie Trilling and Maya Bialik. The following is from the section, “Metacognition—Reflecting on Learning Goals, Strategies, and Results.”

Metacognition, simply put, is the process of thinking about thinking. It is important in every aspect of school and life, since it involves self-reflection on one’s current position, future goals, potential actions and strategies, and results. At its core, it is a basic survival strategy, and has been shown to be present even in rats.

Perhaps the most important reason for developing metacognition is that it can improve the application of knowledge, skills, and character qualities in realms beyond the immediate context in which they were learned. This can result in the transfer of competencies across disciplines—important for students preparing for real-life situations where clear-cut divisions of disciplines fall away and one must select competencies from the entire gamut of their experience to effectively apply them to the challenges at hand. Even within academic settings, it is valuable—and often necessary—to apply principles and methods across disciplinary lines.

Transfer can also be necessary within a discipline, such as when a particular idea or skill was learned with one example, but students must know how to apply it to another task to complete their homework or exams, or to a different context. Transfer is the ultimate goal of all education, as students are expected to internalize what they learn in school and apply it to life.

. . .

3. Verbalization of explanations of verbal or nonverbal knowledge (such as explaining how one makes use of the rhetorical structures of a story as one reads).

Only this third level of metacognitive process has been linked to improved results in problem solving.

Metacognition can be developed in students in the context of their current goals and can enhance their learning of competencies as well as transfer of learning, no matter their starting achievement level. In fact, it may be most useful for lower-achieving students, as the higher-achieving students are already employing strategies that have proven successful for them. For learning disabled and low – achieving students, metacognitive training has been shown to improve behavior more effectively than traditional attention-control training.

2. “MAKING READINGS”

We can think differently–even playfully–about “making readings” of texts. From my secondary classroom, I share the attached video–a reading of Hamlet–as a starting point for a conversation about reading the text differently in and for today’s world.

3. “WRITING THE TEXT INTO THE WORLD”

How can students “write the text into their world”? Here’s one collaborative, multi-modal response from some of my former students.

4. TEXT SELECTION

WHAT we read matters, as does HOW we read. Considerations regarding text selection complement this site’s focus on reading shifts, including reading-for-transfer.

Literary texts inform thinking and affect the way people read the world. When certain perspectives are over-represented, a reader is given a skewed perspective on the world. When perspectives are under-represented (or not represented), the reader lacks awareness of the whole picture.

A person’s reading of the world is best informed by the consideration of many perspectives and many voices. These perspectives and voices can include racial, cultural and religious perspectives; socioeconomic perspectives; geographical perspectives; historical perspectives; and more.

As the reader considers and assimilates additional perspectives offered through a plurality of voices, the reader’s understanding expands. The reader is able to see how narratives complement and also contradict one another. The reader develops a more complete worldview.

Rather than remaining entrenched in one perspective, the reader who encounters many texts is challenged to adapt previously held perspectives based on a more complete reading of “the full text”–the full world. The reader’s enhanced reading can then transfer to other literacy acts.

Following this line of reasoning, one might argue that classic works of literature should be discarded and replaced. After all, these texts often offer dominant and over-represented perspectives. On the surface, this is true. But before we replace these books altogether, we should also ask: Why has the reading of these texts endured across hundreds and even thousands of years? What lies below the surface of cultural perspective?

Classic texts are often full of ambiguity that can allow for complex readings–and valuable learning experiences–that reach far beyond questions of cultural perspective. When we approach old texts from new angles and when we put new lenses on them, we can also read them in entirely new ways. We can find valuable insights offered beneath the apparent surface text.

This site aims to show how shifting the ways we approach all reading texts, including those traditionally included in the literary canon, can allow for deeper and more meaningful reading experiences. This site focuses on the importance of acquiring and using enhanced reading skills that are informed by the reading of many different texts, skills that transfer from texts into the world.

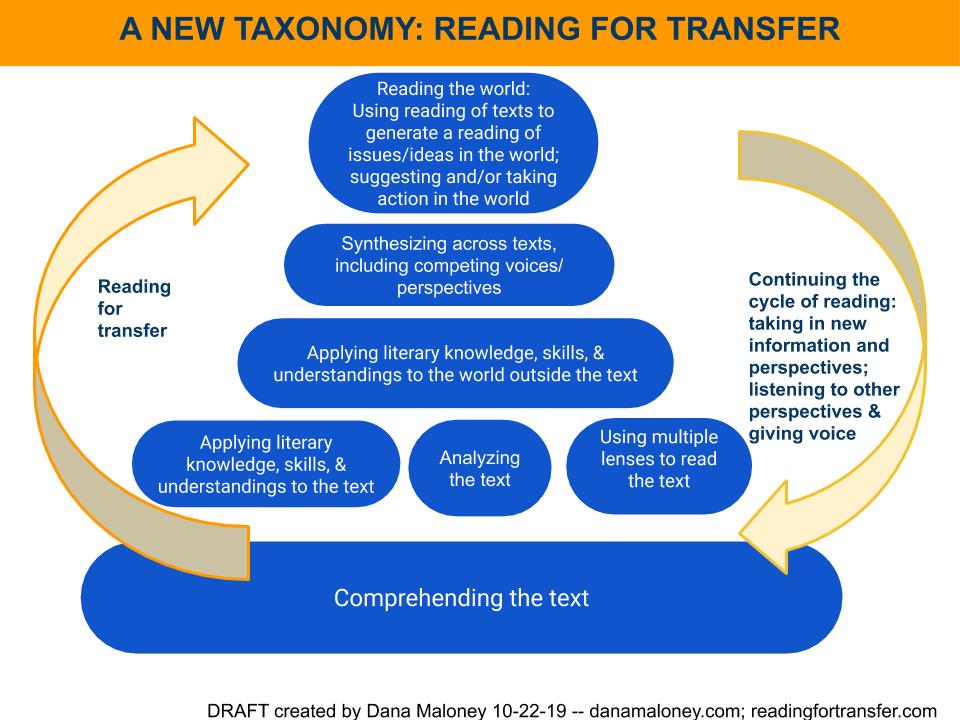

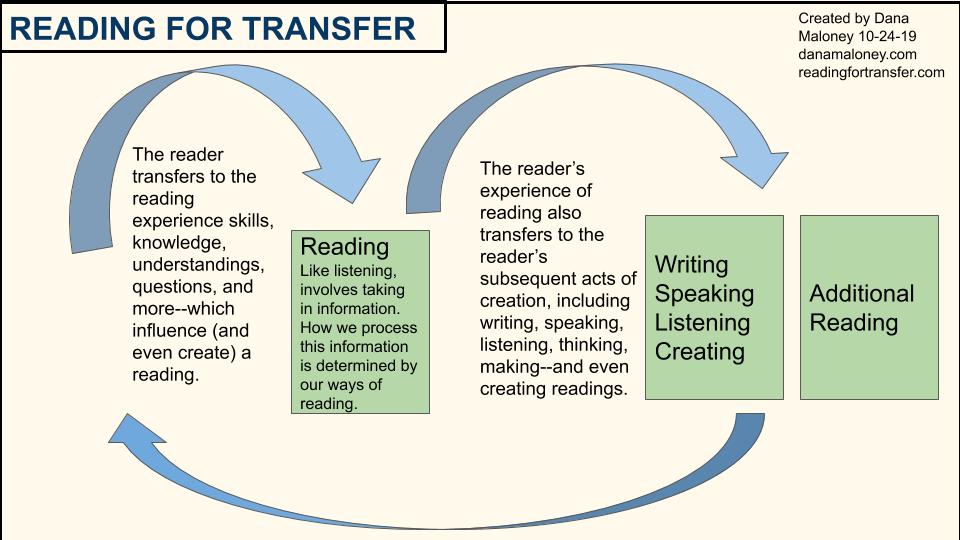

5. REVISING THE READING TAXONOMY